De Casibus Tragödie

On Seneca, Mussato, Trevet and the Boethian “Tragedies” of the De casibus hile good work has been done on the so-called Paduan prehu- manists since Billanovich put them in the critical spotlight half a century ago, 1. A dramatic composition, often in verse, dealing with a serious or somber theme, typically that of a great person destined through a flaw of character or conflict with some overpowering force, as fate or society, to downfall or destruction. The branch of the drama that is concerned with this form of composition.

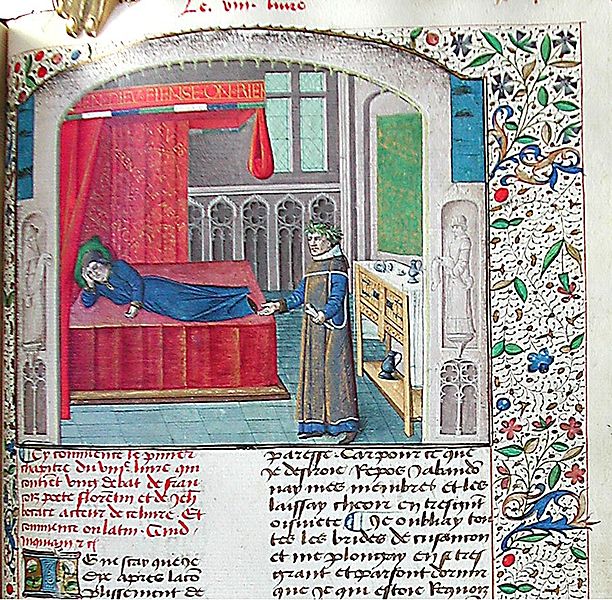

Fortuna. From John Lydgate, The hystorye sege and dystruccyon of Troy, London, 1513. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The medieval concept of tragedy was quite different from that of classical literature. Tragedy was less the result of individual action than a reflection of the inevitable turning of Fortune's wheel.

In the illustration, Fortune, traditionally female because of the association of women with the moon and changeability, stands behind the wheel with outstretched wings. She continually moves the Wheel--on which at the top is a king, at the bottom a beggar.

- More on Renaissance conceptions of tragedy*,

- More about the philosophical roots of Medieval tragedy in Boethius*.

Sad stories. . .

Chaucer's monk, reacting against the assumption of the Host that he will tell a tale of action and love, relates a series of anecdotes about those who fell from happiness to misfortune at the moment they least expected it*.

Such stories are known as de casibus tragedies, after the work by Boccaccio, De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Examples of Famous Men), which is a collection of moral stories of those who fell from the heights of happiness. Both Shakespeare and Marlowe* created characters aware of the de casibus tradition.

On his return from Ireland, Shakespeare's Richard II likens himself to one of those whom Fortune has punished. (Click for more*.)

Footnotes

Lydgate and The fall of Princes

John Lydgate, writing a generation after Chaucer, wrote a long poem, The Fall of Princes, in the same tradition. It is a translation of a French work, which itself is based on Boccaccio.

A Marlovian hero falls

Marlowe's tragedy of Edward II has a character, Mortimer, who mounts to great power as Edward falls. At the end of the play, Edward's son, Edward III, takes over, and has Mortimer executed for the death of his father. Mortimer, in a manner typical of Marlowe's heroes, dies defiantly:

Base Fortune, now I see, that in thy wheel

There is a point, to which when men aspire,

They tumble headlong down: that point I touched,

And, seeing there was no place to mount up higher,

Why should I grieve at my declining fall?

(5.6.59-63). . . Of the death of kings

For God's sake let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings:

How some have been deposed, some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed,

All murdered.

(Richard II, 3.2.155-160)A medieval historian, Adam of Usk, also described the fate of Richard II as a tragedy of fortune:

Though well endowed as Solomon, though fair as Absalom, . . . yet . . . didst thou in the midst of thy glory, as Fortune turned her wheel, fall most miserably into the hands of Duke Henry, amid the curses of thy people.

Lessons in tragedy

In medieval works, the tragedy of those who fell was often less the result of any failing in their lives or actions than the result of the capriciousness of Fortune. But by the Renaissance, the moral effectiveness of pointing out the dire result of vice and sin meant that the protagonists were more often shown to be responsible for their falls.

The best, and most popular example of the genre in the renaissance is A Mirror for Magistrates, Wherein may be seen by example of others, with how grievous plagues vices are punished; and how frail and unstable worldly prosperity is found, even of those whom Fortune seemeth most highly to favour. The Mirror was published in 1559, and many times after.

Boethius' Consolation

The Consolations of Philosophy, written by the sixth century statesman and philosopher Boethius, was a profoundly influential work, translated by Chaucer, and used as the philosophical basis of one of Boccaccio's most read works, De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (Stories of Famous Men), where the lives of those whose fortune changed abruptly from success to failure or death are told.

Boethius argued that the turns of Fortune's Wheel are both inevitable and providential--that is, even the most coincidental of events is actually part of God's plan. Thus the character of the individual is no more important in deciding fate than the influence of the stars, since both are agents of God's will.

Boccaccio

A contemporary of Petrarch, Boccaccio's importance to Shakespeare was in the stories from the Decameron which he used in a number of his plays. In each case, however, he could have found the story in an English version.

Copy Citation

Export Citation

With a personal account, you can read up to 100 articles each month for free.

Already have an account? Login

Monthly Plan

- Access everything in the JPASS collection

- Read the full-text of every article

- Download up to 10 article PDFs to save and keep

Yearly Plan

- Access everything in the JPASS collection

- Read the full-text of every article

- Download up to 120 article PDFs to save and keep

Purchase a PDF

Purchase this issue for $26.00 USD. Go to Table of Contents.

How does it work?

- Select a purchase option.

- Check out using a credit card or bank account with PayPal.

- Read your article online and download the PDF from your email or your account.

- Access supplemental materials and multimedia.

- Unlimited access to purchased articles.

- Ability to save and export citations.

- Custom alerts when new content is added.

Founded in 1966, The Chaucer Review: A Journal of Medieval Studies and Literary Criticism publishes studies of the language, sources, historical and political contexts, social milieus, and aesthetics of Chaucer's poetry, as well as associated studies on medieval literature, philosophy, theology, and mythography relevant to an understanding of the poet, his contemporaries, his predecessors, and his audiences. The Chaucer Review is published quarterly by the Pennsylvania State University Press. Its editors are Susanna Fein (Kent State University) and David Raybin (Eastern Illinois University). As the leading journal of Chaucerian literary criticism, The Chaucer Review acts as a forum for the presentation of research on and concepts about Chaucer and the literature of the Middle Ages.

Part of the Pennsylvania State University and a division of the Penn State University Libraries and Scholarly Communications, Penn State University Press serves the University community, the citizens of Pennsylvania, and scholars worldwide by advancing scholarly communication in the core liberal arts disciplines of the humanities and social sciences. The Press unites with alumni, friends, faculty, and staff to chronicle the University's life and history. And as part of a land-grant and state-supported institution, the Press develops both scholarly and popular publications about Pennsylvania, all designed to foster a better understanding of the state's history, culture, and environment.

De Casibus Trag Cu

This item is part of a JSTOR Collection.

For terms and use, please refer to our Terms and Conditions

The Chaucer Review © 1989 Penn State University Press

Request Permissions